NORTH SEA (2014)

Outside and inside form a dialectic of division, the obvious geometry of which blinds us as soon as we bring it into play in metaphorical domains.

– Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (1994)

The river is the locality of journeying. The river is the journeying of locality.

– Martin Heidegger, Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister” (1996)

Dislocation and de-location are notable threads in Shinwook Kim’s Messenger films. When he is not studying, Kim works as a tour guide, ferrying passengers to and from London airports. Grass Messenger (2013), Ferryman (2014) and North Sea (2014) have all evolved out of his experiences. The Messenger (2013), which is something of a prelude to the series, records Kim’s life on the road, perpetually in transit and dis-placed.

Kim also draws on French anthropologist Marc Augé’s theory of ‘non-places’ to conceptualise his work. In his seminal text, An Introduction to Supermodernity, Augé cites airports and motorways as examples of non-places. For a filmmaker who spends many of his hours travelling on motorways between airports, this theory is understandably stimulating. Kim uses the floating, deterritorialised (and deterritorialising) medium of film to meditate on the dialectical relationship between inside and outside, and between place and non-place.

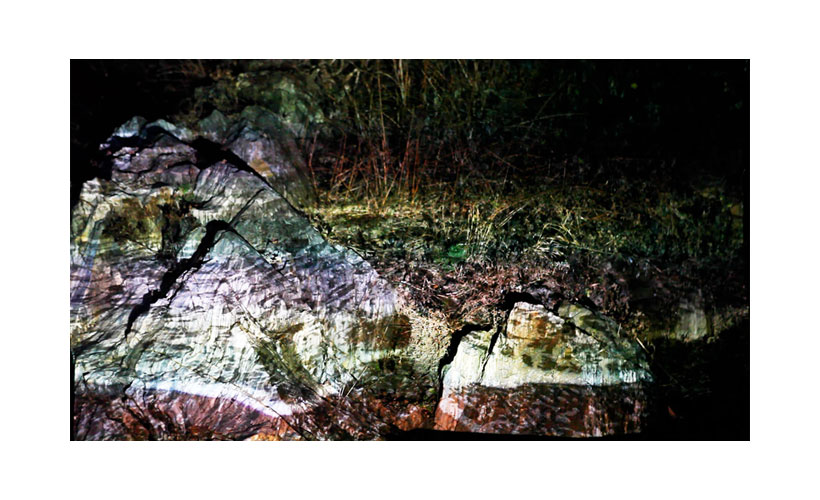

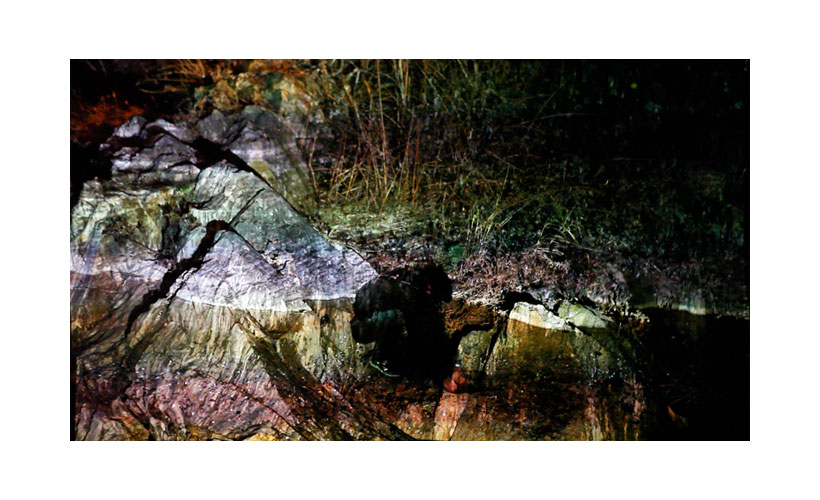

In Grass Messenger (2013), Kim grafts earth from his own garden in London onto either side of the road (and non-place) that divides Belgium and Germany. He then removes earth from this borderland and replants it in his garden, and finally projects his recording of the operation onto the face of a mountain in his native Korea. North Sea (2014) follows a kindred storyline, although the artist’s attempts to transfer sand from his garden onto the Dutch North Sea shore are met with the dislocating force of swash and backwash.

By secretly moving earth between countries at night, and by embedding projected recordings of these clandestine operations into his films, Kim repeatedly conjoins foreign landscapes and thus enmeshes inside and outside. And as one scene is overlaid with another, the artist’s image becomes distorted. Glimmering and kaleidoscopic, yet shadowy and vague, he moves fluidly through these interwoven landscapes.

Alluding to the transportation of souls (in limbo) along the River Styx in Greek mythology, Ferryman’s embedded footage of a boat passing between Belgium and Holland is projected onto the wall of a mountain cave. Like roads, bodies of water provide connections between places, but their own status as places is uncertain. Although politically and topographically defined, they are also constantly shifting and transforming.

Heidegger, in his documented lecture series Hölderlin’s Hymn “The Ister,” tells us that ‘rivers vanish and are full of intimation.’ And in this respect, they share the magnetic and fascinating qualities of film. With its ebb and flow of colours and decibels, the flickering film screen, like the river channel, seems always on the verge of being filled and emptied, fluctuating between bounty and desolation.

When recorded on film, a scene can be animated and recontextualised infinitely and anywhere. As Kim infuses places with the sights and sounds of non-places, and as he merges inside and outside on camera, he offers us a glimpse of the world in a grain of sand.

Ralph Day